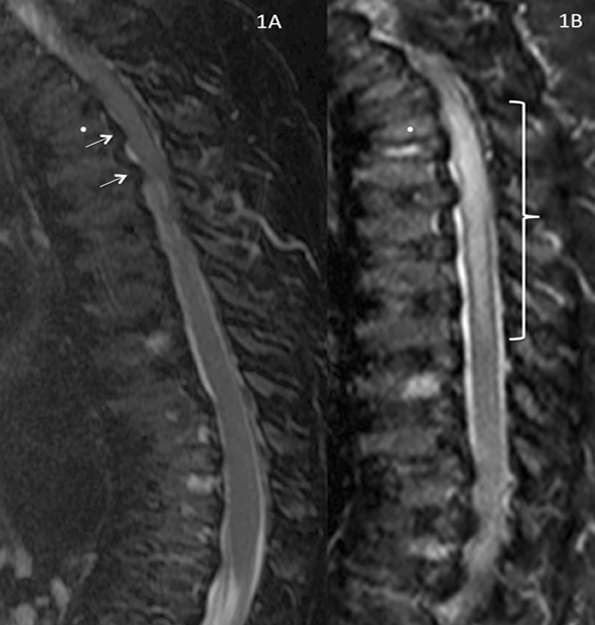

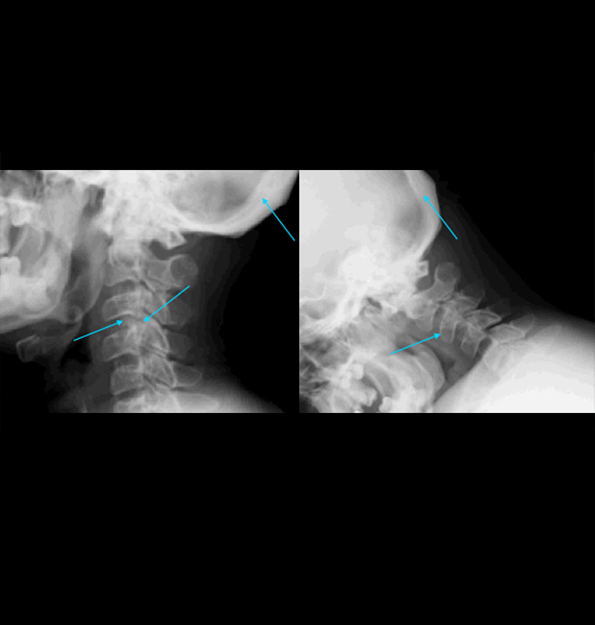

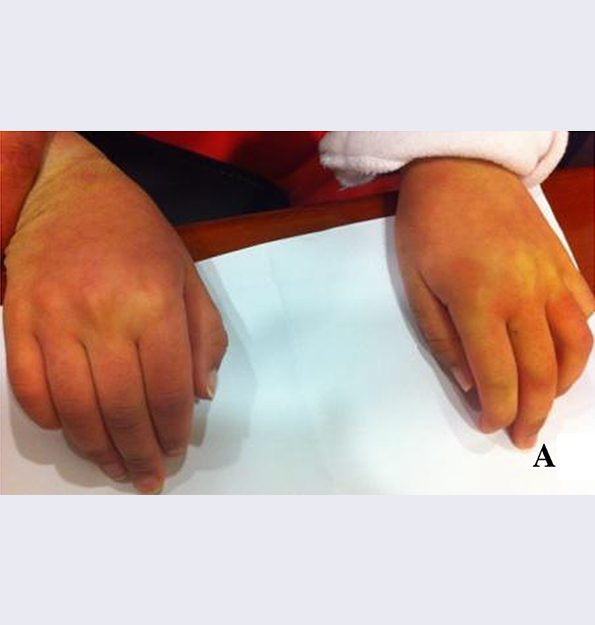

References: 1. Lehman TJA, Miller N, Norquist B, Underhill L, Keutzer J. Diagnosis of the mucopolysaccharidoses. Rheumatology. 2011;50(suppl 5):v41-v48. 2. Hendriksz C. Improved diagnostic procedures in attenuated mucopolysaccharidosis. Br J Hosp Med. 2011;72(2):91-95. 3. Hendriksz CJ, Al-Jawad M, Berger KI, et al. Clinical overview and treatment options for non-skeletal manifestations of mucopolysaccharidosis type IVA. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2013;36(2):309-322. doi:10.1007/s10545-012-9459-0. 4. Engel PA, Bagal S, Broback M, Boice N. Physician and patient perceptions regarding physician training in rare diseases: the need for stronger educational initiatives for physicians. J Rare Disord. 2013;1(2):1-15. 5. Clarke LA, Winchester B, Giugliani R, Tylki-Szymańska A, Amartino H. Biomarkers for the mucopolysaccharidoses: discovery and clinical utility. Mol Genet Metab. 2012;106(4):396-402. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2012.05.003. 6. Muenzer J, Beck M, Eng CM, et al. Long-term, open-labeled extension study of idursulfase in the treatment of Hunter syndrome. Genet Med. 2011;13(2):95-101. doi:10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181fea459. 7. Muenzer J. Early initiation of enzyme replacement therapy for the mucopolysaccharidoses. Mol Genet Metab. 2014;111(2):63-72. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2013.11.015. 8. Muenzer J, Wraith JE, Clarke LA, International Consensus Panel on the Management and Treatment of Mucopolysaccharidosis I. Mucopolysaccharidosis I: management and treatment guidelines. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):19-29. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-0416. 9. Clarke LA. Pathogenesis of skeletal and connective tissue involvement in the mucopolysaccharidoses: glycosaminoglycan storage is merely the instigator. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50(suppl 5):v13-18. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/ker395. 10. Morishita K, Petty RE. Musculoskeletal manifestations of mucopolysaccharidoses. Rheumatology. 2011;50(suppl 5):v19-v25. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/ker397. 11. Hendriksz CJ, Berger KI, Giugliani R, et al. International guidelines for the management and treatment of Morquio A syndrome. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2014;9999A:1-15. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.36833. 12. Berger KI, Fagondes SC, Giugliani R, et al. Respiratory and sleep disorders in mucopolysaccharidosis. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2013;36(2):201-210. doi:10.1007/s10545-012-9555-1. 13. Spinello CM, Novello LM, Pitino S, et al. Anesthetic management in mucopolysaccharidoses. ISRN Anesthesiol. 2013;2013:1-10. doi:10.1155/2013/791983. 14. Lampe C. Attenuated mucopolysaccharidosis: are you missing this debilitating condition? Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012;51(3):401-402. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/ker375. 15. Tomatsu S, Montaño AM, Oikawa H, et al. Mucopolysaccharidosis type IVA (Morquio A disease): clinical review and current treatment: a special review. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2011;12(6):931-945. doi:1389-2010/11. 16. Lachman RS, Burton BK, Clarke LA, et al. Mucopolysaccharidosis IVA (Morquio A syndrome) and VI (Maroteaux-Lamy syndrome): under-recognized and challenging to diagnose. Skeletal Radiol. 2014;43(3):359-369. doi:10.1007/s00256-013-1797-y. 17. Montaño AM, Tomatsu S, Gottesman GS, Smith M, Orii T. International Morquio A Registry: clinical manifestation and natural course of Morquio A disease. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2007;30(2):165-174. doi:10.1007/s10545-007-0529-7. 18. Thümler A, Miebach E, Lampe C, et al. Clinical characteristics of adults with slowly progressing mucopolysaccharidosis VI: a case series. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2012;35(6):1071-1079. doi:10.1007/s10545-012-9474-1. 19. Muenzer J. The mucopolysaccharidoses: a heterogeneous group of disorders with variable pediatric presentations. J Pediatr. 2004;144(suppl 5):S27-S34. 20. Kinirons MJ, Nelson J. Dental findings in mucopolysaccharidosis type IV A (Morquio’s disease type A). Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990;70(2):176-179. 21. Lachman R, Martin KW, Castro S, Basto MA, Adams A, Teles EL. Radiologic and neuroradiologic findings in the mucopolysaccharidoses. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. 2010;3(2):109-118. doi:10.3233/PRM-2010-0115. 22. Cimaz R, Coppa GV, Koné-Paut I, et al. Joint contractures in the absence of inflammation may indicate mucopolysaccharidosis [hypothesis]. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2009;7:18. doi:10.1186/1546-0096-7-18. 23. Fahnehjelm KT, Ashworth JL, Pitz S, et al. Clinical guidelines for diagnosing and managing ocular manifestations in children with mucopolysaccharidosis. Acta Ophthalmol. 2012;90(7):595-602. doi:10.1111/j.1755-3768.2011.02280.x. 24. Zafeiriou DI, Batzios SP. Brain and spinal MR imaging findings in mucopolysaccharidoses: a review. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34(1):5-13. doi:10.3174/ajnr.A2832. 25. Braunlin EA, Harmatz PR, Scarpa M, et al. Cardiac disease in patients with mucopolysaccharidosis: presentation, diagnosis and management. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2011;34(6):1183-1197. doi:10.1007/s10545-011-9359-8. 26. Braunlin E, Orchard PJ, Whitley CB, Schroeder L, Reed RC, Manivel JC. Unexpected coronary artery findings in mucopolysaccharidosis. Report of four cases and literature review. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2014;23(3):145-151. doi:10.1016/j.carpath.2014.01.001. 27. Mesolella M, Cimmino M, Cantone E, et al. Management of otolaryngological manifestations in mucopolysaccharidoses: our experience. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2013;33(4):267-272. 28. Martins AM, Dualibi AP, Norato D, et al. Guidelines for the management of mucopolysaccharidosis type I. J Pediatr. 2009;155(4)(suppl 2):S32-S46. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.07.005. 29. Wood TC, Harvey K, Beck M, et al. Diagnosing mucopolysaccharidosis IVA. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2013;36(2):293-307. doi:10.1007/s10545-013-9587-1. 30. Data on file. Biomarin Pharmaceutical, Inc. 31. Drummond JC, Krane EJ, Tomatsu S, Theroux MC, Lee RR. Paraplegia after epidural-general anesthesia in a Morquio patient with moderate thoracic spinal stenosis. Can J Anesth. 2015;62(1):45-49. doi:10.1007/s12630-014-0247-1. 32. Sharkia R, Mahajnah M, Zalan A, Sourlis C, Bauer P, Schöls L. Sanfilippo type A: new clinical manifestations and neuro-imaging findings in patients from the same family in Israel: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014;8:78. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-8-78. 33. Heese BA. Current strategies in the management of lysosomal storage diseases. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2008;15(3):119-126. doi:10.1016/j.spen.2008.05.005. 34. Kakkis ED. Enzyme replacement therapy for the mucopolysaccharide storage disorders. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2002;11(5):675-685. 35. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Defining the PCMH. https://pcmh.ahrq.gov/page/defining-pcmh. Accessed December 15, 2015. 36. Hwu W-L, Okuyama T, But WM, et al. Current diagnosis and management of mucopolysaccharidosis VI in the Asia-Pacific region. Mol Genet Metab. 2012;107(1-2):136-144. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2012.07.019. 37. Klitzner TS, Rabbitt LA, Chang RKR. Benefits of care coordination for children with complex disease: a pilot medical home project in a resident teaching clinic. J Pediatr. 2010;156(6):1006-1010. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.12.012. 38. Mosquera RA, Avritscher EBC, Samuels CL, et al. Effect of an enhanced medical home on serious illness and cost of care among high-risk children with chronic illness: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312(24):2640-2648. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.16419.